A presentation by Bill Thompson to the Vintage Reds ACT on Tuesday 17 September 2019 at the Tradies Club, Dickson ACT 1

Bill acknowledged the Ngunnawal people, the custodians of this land and the land on which we met, and paid his respects to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples past and present.

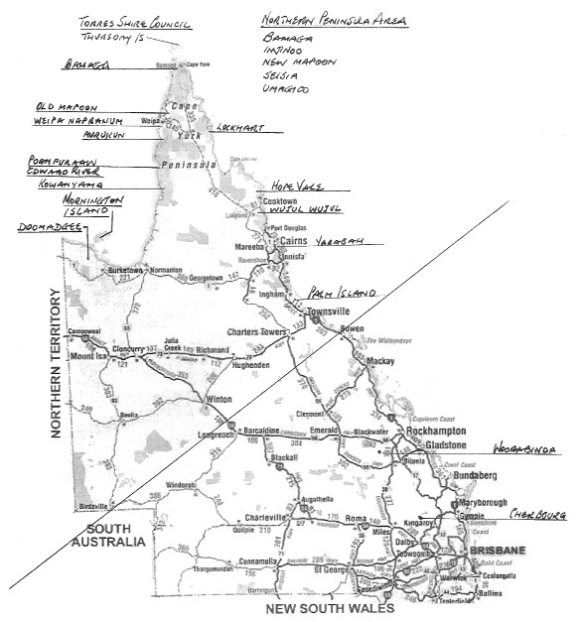

I was appointed as the North Queensland Organiser by the Municipal Officers Association (MOA), Queensland Branch, in July 1985. The union later to merged with others to form the Australian Services Union. My area of responsibility was the northern half of Queensland, or that area above a line drawn between Birdsville inland to Bowen on the coast.

It was a difficult time to be appointed, as the South East Queensland Electricity Board industrial dispute had been raging (and that is not too strong a word) for five months, and it was the year in which great changes were occurring in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community councils, not the least in their governance. With the introduction of the Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT), a significant disruption in the administration of those councils had occurred.

Much of what follows is anecdotal and personal observations. But here I must digress.

Have you heard the joke about the bloke who went to the doctor – he had a monkey growing out of his head. Tell me said the doctor, “how did this begin?” Well, said the monkey, “it started with a spot on my bottom’. At the risk now of enraging the Queenslanders in the room, I need to set the political scene in Queensland in 1985.

“Rural, backward, racist, populist, authoritarian and corrupt”. So said Seymour Martin Lipset an American political scientist, who in the context of the USA said “every country has a South”. We in Australia have a North, in this case Queensland under the Bjelke-Petersen Government, which had been in office since 1968. The definition suited Queensland to a ‘T’, as the Liberal-Country Party (later the Liberal National Party), well entrenched both politically and within that society, was resolutely opposed to change, unless it was to the detriment of its political enemies. Queensland was to prove the political monkey on the back (not the head) of the Australian body politic for decades. No doubt, a sentiment shared by Gough Whitlam.

Now to return to the actual circumstances.

A white-collar local government union, the MOA had been eager to extend its coverage of its federal industrial award, into Queensland community councils. In one respect it was a defensive move as it feared that in its absence the Australian Workers Union (AWU), a state registered body, would try and fill the vacuum with an amendment to its state award, knowing full well the Bjelke-Peterson Government would readily concur. Both wanted a Queensland state award with the AWU respondent.

The AWU Queensland Branch had form. It had colluded with successive state governments, including Labor governments, ever since the disastrous shearers’ strike of 1891. The MOA had made application to the then federal industrial body, the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission, to register what was later to become the Municipal Officers Aboriginal and Islanders Community Councils Award 1985, a proposal that reflected the existing industrial circumstances elsewhere in Queensland local governments.

On the penultimate hearing day at the Federal Industrial Commission, the state government industrial advocates, who had registered as a party to the hearing, were shown a number of documents by one of the MOA representatives after the close of the hearing. The documents were not tabled and therefore off the record. Their content is unknown. We do know that on that hearing day, the lights in the Premier’s Office burned long into the night.

On the following hearing day the State Government capitulated and the case for the AWU collapsed. The MOA had a new federal award to which it was respondent. The contents of the documents have never been disclosed and as far as I am aware only one person amongst the MOA advocates knows what was divulged, and he is not telling.

Once handed down, it turned out that the work of implementation of the new award by the MOA had just begun. My area of responsibility included most of the Aboriginal and Islander councils in North Queensland: about twenty communities on the mainland or adjacent to it, and ten in the Torres Strait north of the tip of Cape York Peninsula. With limited resources at my disposal, and because they were more accessible, I gave the mainland communities my priority, and I deferred incurring the great travel expenses involved in organising communities in the Torres Strait. This it should be noted was additional to another twenty or more city and shire councils covered by the main local government industrial award. The newly amalgamated Australian Services Union fully supported the efforts of the former MOA to implement its new award.

To illustrate the organising problem, it needs to be noted that the residents of Melbourne reside closer to Brisbane (by air 1381 km) than do the residents of Cairns (by air 1389 km) and if you fly from Brisbane to Thursday Island and stop off at Townsville where I was based, over 1100 km north, you are only halfway there. Australia is truly a big country!

To illustrate the organising problem, it needs to be noted that the residents of Melbourne reside closer to Brisbane (by air 1381 km) than do the residents of Cairns (by air 1389 km) and if you fly from Brisbane to Thursday Island and stop off at Townsville where I was based, over 1100 km north, you are only halfway there. Australia is truly a big country!

There was a good history of union support in some of the places I was to visit. Palm Island had a very favourable community view of trade unions who had assisted them in opposing a very oppressive and reactionary government administration in the 1950s. A very resourceful, self-appointed and unofficial steward had emerged amongst the employees of Aurukun Shire Council and he had managed to sign up most of those who were eligible for MOA coverage. He argued with his workmates that if you wanted union representation and union organisers to visit then you needed to join the union and remain financial. These were the exception. Elsewhere in remote Queensland communities it turned out all too frequently to be a hard slog.

It was soon apparent that the best way to visit was to share expenses with other unions, either vehicle hire or air charter. Selecting the persons to accompany me was critical. I did not want to compete with union officials who wanted to monopolise the time that I needed to talk with council administrative and supervisory staff, and I had logistical responsibilities for the trip. When air charters were involved ground transport was essential, and in this regard the Queensland Nurses Union organisers and their members on the ground were invaluable, bless them. They always had transport available and were very generous with it.

Over the years I was also accompanied by Aboriginal liaison officers appointed by the Queensland Trades and Labour Council, public servants from industrial relations departments (an early mistake as they wanted to monopolise the ear of the senior council staff too), and the other unions. A party of three in a vehicle, but six at a maximum for an air charter. It should be noted that these were small communities with small staffs who could be overwhelmed by a larger number of visitors. The trips usually lasted about twelve days.

Whilst English was the lingua franca, in the communities one or more indigenous languages might co-exist domestically. In the earlier era of religious missions most of the Christian faiths were represented. Invariably, most of the communities had been dispossessed from their traditional country, taken over by rent-seeking commercial interests, such as pastoralists and miners seeking profits.

This dislocation, the mission’s forced severance of traditional cultural practices, and the lack of administrative leadership training, all too frequently contributed to any dysfunction in the community. Sadly this continues to be emphasised in the tabloid press to this day. To their credit, some of the missions resisted the Bjelke-Petersen’s Government’s ‘assimilation policy’ and supported indigenous land rights. By the 1980s the mission’s financial situation were in a parlous state and the state government was compelled to intervene. Community health, housing, education and staffing costs increased and self-sufficiency decreased. Over time all went broke. In the absence of divine intervention and with no way of privatising the community’s assets, the losses had to be socialised. The taxpayer to the rescue.

I will now go ‘around the map’ of Queensland and make a few comments about some of the communities which I visited over the years. Beginning in the north-west.4

Mornington Island

Located 28 km off the coast in the Gulf of Carpentaria and occupied by the Lardil people, the traditional owners of Mornington Island, it is the largest in the group of Wellesley Islands. Most reside in the community centre of Gununa, together with the Kaiadilt and Yangkaal people, the traditional custodians of several of the smaller islands between Mornington Island and the mainland. In earlier times it was a Presbyterian Mission. The population is about 1143 (2016). It is noted for its cultural revival in the 1960s where residents became noted artists and dancers. It is connected to Burketown by air.

Doomadgee

Some 93 km west of Burketown by road, on the banks of the Nicholson River. Doomadgee had an unreliable water source until the Goss Government constructed a weir to provide a year round supply. The community’s traditional owners are the Waanyi and Gangalidda people with three additional indigenous languages spoken domestically. It was earlier a Christian Brethren Assemblies Mission. Its population was about 800 in 1985.

Kowanyama

Near the banks of the South Mitchell River on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula. The traditional owners, the Kokoberra, Yir Yoront and Kunjen clans have a distinct language and culture. A mission was conducted by the Church of England who resisted the predations of the local pastoralists who abducted and kidnapped the local inhabitants to supplement their labour requirements. Later the mission itself was to become a major cattle station and a supplier of skilled stockmen and domestic servants. Its population in the 2016 Census was 944 people.

Pormpuraaw

Established as the Edward River Mission 500 km from the tip of Cape York Peninsula, on the west coast by the Anglican Church. It is the home of the Thaayore, Wik, Bakanh and Yir Yeront people, who boast of the best fishing on the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria. Crocodile farming is a growing enterprise. Its population was 749 in 2016.

Aurukun

One of the largest communities on the Peninsula, at the confluence of the Archer, Watson and Ward rivers. Crocodiles abound. It is accessible by road 200 km north to Weipa. The traditional owners are the Wik and Wik Way people and in addition there are five language clan groups. Aurukun was the site of a Presbyterian Mission and was known as an early abuser of the indigenous peoples. Outside the present council offices there existed, when I last visited, the ‘whipping tree’ where indigenous recalcitrants were punished. The northern section of the reserve were excised to Comalco when it was granted a bauxite lease, the base ore for refining into aluminium. The Mapoon Mission was also Presbyterian and was similarly dealt with. (See below). The excision and other high-handed action resulted in much litigation with the Bjelke-Petersen Government, including the government’s leasing out traditional lands exclusively to pastoralists and miners. The ‘Wik’ case resolved the issue in favour of the Wik people of the Aurukun region, who established an equal entitlement to their lands. Their agreement to the use of their land now had to be obtained. The population of Aurukun in 1983 was 880 (ABS).

Napranum

Sometimes referred to as Weipa-Napranum or Weipa South, Napranum was established as a Presbyterian Mission for the traditional owners, the Alngith (Al-Nith) people. The community has three major sub-groups and some descendants of South Sea Islanders. Its proximity to the major mining operation of Comalco has resulted in a fractious though sometimes beneficial history. Many residents are employees of the company and the Napranum Council successfully tendered for the construction of about 30 km of cattle fencing around the Scherger RAAF Forward Deployment Base 25 km to the east of Weipa.

Mapoon

Mapoon is located 75 km north of Weipa on the west coast of the Peninsula near Port Musgrave. Its Presbyterian Mission, also known as the Batavia River Mission, was established in 1891, when it grew fruit and vegetable crops and raised a cattle herd. In 1954 about 285 persons were resident at Mapoon. It has a sad history of dispossession of the land owners from their traditional lands, when the Queensland Government’s Director of Native Affairs, Patrick Killoran, notoriously conspired with Comalco, a bauxite refiner, to excise 8000 square kilometres from their mission reserve. Moved forcibly in 1963 by armed police, who set fire to their homes and their church, the remaining 23 of 94 residents were then despatched by barge 200 km north to Bamaga into the settlement that became New Mapoon. Former Uniting Church President Sir Roland Wilson in 1990 apologised to the Mapoon people for his predecessor’s flagrant human rights abuse. Subsequently, many residents returned to ‘Old Mapoon’ to resettle and redevelop the area. Their return to what was an unofficial community has now been formally recognised as ‘official’. The Premier Peter Beatty offered an apology to the people of Mapoon in 2001, on behalf of all Queenslanders. The bauxite miner Comalco has offered recurring financial support to the community. The population in 2011 was 263 persons. See New Mapoon below.

Northern Peninsula Communities

Bamaga refers both to the area now known as the Northern Peninsular Communities and what was formerly known as the Bamaga community Council, one of five communities located just south of the tip of Cape York Peninsula. The NPA peoples’ history is a story of dislocation and relocation. Bamaga is now the administrative centre for the NPA and it hosts the only secondary boarding school in Cape York Peninsula. Comprising five communities, Injinoo, Umagico, New Mapoon, Seisia and Bamaga, they amalgamated in 2007 to form the NPA. The indigenous languages spoken include Atambaya, Gudang, Yadhaykenu, Ankamuthi, Wuthathi and Kaurareg. In 2008 the five communities evolved into an amalgamated Northern Peninsular Area Regional Council. It is serviced by the Bamaga Airport some 25 km to the south. In 2016 the NPA had a population of 2796.

Bamaga

Bamaga takes its name from Bamaga Ginau, a Saibai Islander who initiated the evacuation of residents to the mainland, after a storm surge in the Torres Strait in 1947 inundated the island, causing property damage and salting of the soil.5

Injinoo

The Queensland Government admits officially in an 1896 report that the estimated Aboriginal population in the 1870s was about 3000 persons. By 1896, the number had fallen to an estimated 300, and the “tribe which held the country from Somerset to [the tip of] Cape York (was now) extinct”. The causes given included “introduced diseases, exclusion from traditional hunting grounds and frontier violence”. Injinoo, also known as Cowal Creek, housed an Anglican Mission from 1923. After World War 2, as compensation for their contribution to the War, and as a defence measure, the government encouraged Torres Strait Islanders to resettle on the mainland. Development in the area included construction, agriculture and sawmilling. Cowal Creek Aboriginal Council formed in 1986 and the Injinoo Aboriginal Shire Council in 2005. Short lived, it was absorbed into the Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council in 2008. The community had a population of 561 at the 2016 Census.

New Mapoon

Following their expulsion from ‘Old’ Mapoon in 1963, the community relocated to the Bamaga area, where it developed to become the New Mapoon Aboriginal Council in 1986. In turn, it was to be absorbed into Northern Peninsular Regional Council in 2008. Over the years many of the New Mapoon residents have returned to their first home at Mapoon, where they resettled to unofficially redevelop the area. There has been a subsequent reaccommodating of the parties involved. In 2016 the population was 383.

Seisia

The small Islander community Seisia in the Northern Peninsula Area, situated on the coast, has the wharf for the ferry service to Horn and Thursday islands. It has been the main point of settlement for Islander peoples on the mainland. The principal indigenous languages is Torres Strait Creole and Kala Kawa whilst English is the lingua franca. The Anglican Church was dedicated in 1972. The community was granted its Deed of Grant in Trust in 1987 and was absorbed into the Northern Peninsula Council in 2008. Its population in 2006 was 260 people.

Umagico

In 1963 the government removed 64 Aboriginal people from the Lockhart River (Anglican) Mission to establish Umagico, 449 km by road to the north, and to co-locate them with the Injinoo community, in the Bamaga area. There is also a group of Moa Island people from the western Torres Strait, forming a joint Aboriginal-Islander community. In addition to English there is a variety of indigenous languages spoken. Some people have returned to Lockhart River. (See further comment below.) Granted its Deed of Grant in Trust in 1986, and later in 2008 it formed part of the Northern Peninsula Regional Council. In the Census of 2016 Umagico had a population of 427.

Thursday Island (aka Waiben)

About 40 km north-west of the Cape York Peninsula, the principal Aboriginal group in Thursday Island is the Kaurareg, the traditional owners, who conducted traditional hunting, fishing and horticulture. The pearling industry attracted Japanese divers and the Chinese arrived as traders. Often referred to as ‘TI’, it is the main administrative centre for the people of the 20 adjacent islands forming the Torres Shire Council. In its development, trading with the people of the Cape York Peninsula. The languages spoken reflect the cosmopolitan composition of the TI community. Communications were improved when an under-sea telegraph link was made with Cape York in 1887. Its airport is on the adjacent Horn Island serviced by a ferry and remains dependent for its water supply piped from nearby Prince of Wales Island. It was an important area of operations in World War 2, when its Japanese residents were interned, and many of its civilians sent to the mainland. Established in 1974, the Torres Shire Council has a northern border 73 km from Papua New Guinea with whom customary contact is frequent and visa free. The Council provides the whole range of local government services for its population of 3610 (2016).

Lockhart River

An Aboriginal community located on the east coast of Cape York Peninsula, 592 km north of Cooktown. Lockhart River’s early inhabitants were forcibly removed there from areas of the central Cape. They comprise the Wuthathi, Kuuku Ya’u, Uutaalnganu, Umpila and Kaanju clan groups. An Anglican Mission was established in 1924 and the co-director of co-operatives at the Australian Board of Missions, the Reverend Alf Clint, established a co-operative at Lockhart River in 1954. He held a firm belief that co-operatives were culturally appropriate for Aboriginal communities.In 1963, an Australian Army ‘Operation Blowdown’ exploded 50 tons of TNT to simulate a tactical nuclear weapon detonated in tropical rain forest in the Iron Range National Park, 11 km to the west of Lockhart River. This is part of the most northern tropical rain forest in mainland Queensland. One Australian soldier witness said to me he considered it an act of environmental vandalism as all the results of the explosion were predictable.

By 1967 the transfer of control of the Mission to the Queensland Government was completed with the intention of closing down the Lockhart River facility and the relocation of the residents to Bamaga. A protest followed and the Government relented. The Lockhart River Aboriginal Council was established in 1985, it received its Deed of Grant in Trust two years later, and in 2004 it became the Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council. Its population was 724 persons in the 2016 Census.

Hope Vale

Since 2018, Hope Vale, 73 km north of Cooktown, has been serviced by a sealed road. A Lutheran mission was established initially at Hope Valley in the late 1880s, and uniquely amongst the Cape York communities taught the local people, the Thubi Warra, in their main language, Guugu Yimidhirr. In 1902 the Marie Yamba Mission near Proserpine was closed and its inhabitants moved to 984 km north to Hope Vale. Today the main local industry is cattle grazing. Its first council was elected in 1985 and it received its Deed of Grant in Trust the following year. It is the former home community of Noel Pearson, a graduate of the Lutheran College Brisbane and Sydney University in law and history, an activist and co-founder of the Cape York Land Council.

Wujal Wujal

Wujal Wujal or ’many waterfalls’, some 71 km south of Cooktown, is located on a tiny 19.94 square kilometres of land on the banks of the Bloomfield River, the traditional occupants being the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people. They receive a small financial benefit from tourism, being in the Bloomfield National Park. The present population of 326 (2006 Census) speak several indigenous languages. They have many family and cultural links with the Hope Vale Community, both being Lutheran, and they received their Deed of Grant in Trust in October 1987. In January 2005 they became the Wujal Wujal Aboriginal Shire Council.

Yarrabah

Yarrabah is 50 km by road and about 10km direct by air across Trinity Inlet from Cairns, and was first established as an Anglican, Bellenden-Ker Mission for Gunggandji and Yidinji people. It was later known as Yarrabah, an Anglicised version of the local language name for the area. In the early 20th Century it was declared an Industrial School for ‘neglected’ children and over 100 inhabitants of Fraser Island were forcibly sent here, over 1500 km north. It was evident that many could not be adequately housed, many absconded and were later captured by the police and returned to Yarrabah. This forcible relocation of indigenous people was replicated across Queensland to Palm Island Woorabinda and Cherbourg, amongst other places. A visitor to Yarrabah in 1938 found 43 tribal groups represented. By the late 1950s simmering protest erupted into strike action over inadequate rations, poor working conditions and arbitrary administration. The church at Yarrabah was administering a large social welfare scheme and after representations the state government took over from the Anglicans.7 A Deed of Grant in Trust was issued in October 1986 for an area of 15609 acres.

Palm Island

Hull River Reserve 200km north of Townsville was severely damaged by a cyclone in 1918 and its indigenous inhabitants relocated 150 km south to Palm Island, off the coast 64 km north-west of Townsville. It is one of the more recently established indigenous communities, and was to be a place for recalcitrant, single mothers and those newly released from prison. For over 20 years it was a repository for 1600 people from 40 indigenous groups across Queensland. Strictly regulated, mail was vetted, visitors restricted and nightly curfews imposed. Throughout Queensland mismanagement of indigenous wages by payment of less than award wages was rampant, and on Palm Island it was systematic theft by the odious Aboriginal and Islanders Affairs Department. The Trades and Labour Council of Townsville played a major part in having the matter rectified. Other notorious events include two deaths in custody, one in 1961 and the other in 2004, both involving Queensland police. The work of historians Noel Loos, Rosalind Kidd and Henry Reynolds has played a great part in informing Australia of the deplorable plight of the Aboriginal and Islander peoples generally, and of Queensland in particular. A population now of about 2000 people, when awarded its Deed of Grant in Trust in 1985 the state government sent infrastructure such as the timber mill, farming equipment and housing to the mainland. The malice of the Bjelke-Petersen Government knew no bounds.

Note: Woorabinda and Cherbourg communities were outside the North Queensland Area and the writer has no direct knowledge of them.

A Selective Chronology

1963 Forcible eviction of Mapoon residents begins & the settlement burnt down.

1965 Indigenous people have right to enrol & vote, not compulsory.

1968 Bjelke-Petersen Government elected.

1971 Compulsory voting for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders .

1973 Voting age reduced to 18 years.

1974 Eric Deeral LNP, Member for Cook, first Qld. indigenous person elected.

1985 February, SEQEB Dispute begins, job losses & superannuation foregone.

1985 July, Bill Thompson appointed to MOA.

1985 Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT), applied to 15 councils .

1986 Bjelke-Petersen LNP Government re-elected (to 1 Dec 87). Unemployment 11%, inflation 9%.

1987 ‘Joh for PM’ campaign derails Howard’s bid for government.

1987-89 Bob Katter jnr Minister for Aboriginal & Islander Affairs in the Qld LNP Government.

1987 Ahern LNP Government elected.

1989 Cooper LNP Government.

1989 Goss ALP Government elected. It was to ensure all communities had an assured safe water supply & to seal all roads within the communities, thus contributed greatly to improved community health.

1991 Electoral reform, 89 districts created.

1996 Borbidge LNP Government elected.

1998 Beattie ALP Government elected.

1999 Further electoral redistribution.

2007 Bligh ALP Government.

2012 Newman LNP Government elected.

2015 Palaszczuk ALP Government elected.

Disclaimer: This document has not been peer reviewed. All errors & omissions are those of the writer, & should the content offend any reader, in particular in regard to the deceased, this writer wishes to offer his apology.

2 Author unknown.

3 Lipsett, Political Man: The social basis of politics, Doubleday, New York, 1960.

4 There are two principal sources for the information that follows: 1. State Library of Queensland https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/discover/aboriginal-ans-torres-strait-islander-cultures-and-stories (Accessed 10 Sept. 2019) and, 2. Queensland Government, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islands, ‘Community Histories’ https://www.qld.gov.au/atsi/cultural-awareness-heritage-arts/ (Accessed 10 Sept. 2019).

5 Saibai, together with the islands on Boigu & Duan were excised by Australia from the TPNG by the Torres Strait Treaty of Nov. 1978. See www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs258.aspx Accessed 16 Sept. 2019.

6 Archibald Merston, ‘Report on the Aboriginals of Queensland’ to the Home Secretary, QLD Votes & Proceedings, vol.4, no.1 (1896), p.724, Queensland State Archives, Home Secretary’s Office, HOM/J717, 1929/3999 list of Aboriginal reserves.

7 Yarrabah Aboriginal Shire Council https://www.yarrabah.qld.gov.au/council/history/ Accessed 15 Sept. 2019,