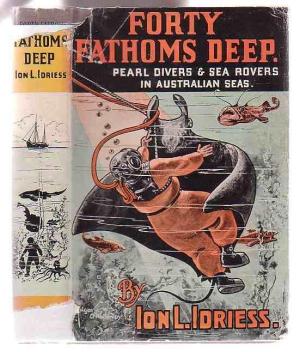

Ion Idriess, Forty Fathoms Deep (Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1937)

Review essay by Pamela Blakeley, December 2019

By the early 1930s Broome in Western Australia was a thriving town, ‘a tiny place, yet the richest and greatest pearling port the world has ever known’. Idriess spent more than a year there and wrote Forty Fathoms Deep based on his own experiences and first-hand information.

The main story is about the romantic,  guitar-playing Castilla Toledo from Manila. He is a young, good-looking diver on Bernard Bardwell’s lugger Phyllis, and he is desperate to find a pearl so that he can marry the white girl of his dreams. Every now and then a pearl is discovered inside the pearl shell which is the basis of the industry. Approximately one pearl shell in 500 contains a natural pearl. At the time a single pearl could fetch hundreds or thousands of pounds in Broome and far more when it was resold in Europe. Bardwell warns Toledo against the girl, an adventuress from down south, and indeed she marries another man as soon as Toledo has put to sea. Toledo finds

guitar-playing Castilla Toledo from Manila. He is a young, good-looking diver on Bernard Bardwell’s lugger Phyllis, and he is desperate to find a pearl so that he can marry the white girl of his dreams. Every now and then a pearl is discovered inside the pearl shell which is the basis of the industry. Approximately one pearl shell in 500 contains a natural pearl. At the time a single pearl could fetch hundreds or thousands of pounds in Broome and far more when it was resold in Europe. Bardwell warns Toledo against the girl, an adventuress from down south, and indeed she marries another man as soon as Toledo has put to sea. Toledo finds

another girl. He still needs a pearl in order to marry.

Toldedo returns to sea and works like a demon, provoking the crew to introduce chilli powder into his lifeline to force him to come up from the bottom of the sea. Towards the close of the season, an unrecognised vessel fishes nearby for several days. Then one afternoon a dinghy comes off her and races towards the lugger. A white man jumps aboard in great excitement. The master immediately takes him down below. The man, naïve in the cunning ways of Broome, has found an exquisite pearl and wants to show it off! The master estimates its worth at over £5000 and suggests showing it to his diver, Toledo. ‘Toldeo’s heart leapt at the sight of the pearl, the world stood still for him.’ They drink and smoke and admire the pearl. They have dinner. Toldeo drinks little himself but keeps the glasses of the two men full. Soon the men are drunk, and the wind has whipped up. The visitor finally wraps the pearl in soft paper, puts it into a match box and, helped by Toledo, takes to his dinghy and rows away unsteadily. However, the pearl is in Toledo’s pocket, the empty matchbox in the pocket of the other man.

So begins a story befitting a gripping crime novel. By the time the precious pearl is lost at sea, there has been one murder, three men have been hanged at Freemantle Gaol for that murder, one man has committed suicide, another has died of premature heart failure and Toledo himself has drowned in a shipwreck after earlier surviving more than 24 hours adrift at sea clinging to a grating.

Idriess meticulously explains the circumstances and relationships between the many races of people who comprised the work force of Broome. The owners and masters of the fleets of pearling luggers were British or Australian and lived apart in pretty, spacious cottages in a line back from the beach. Further inland were the crowded quarters of the Philippinos, Malays, Indonesians, Torres Strait Islanders and Aborigines, South Sea men and the more recent arrivals, the Japanese, who were poised to take over, first, the jobs on the luggers, and later the industry itself. Idriess attributes this to their communal, ambitious, painstaking and fatalistic character. We also meet the sophisticated and cunning itinerant pearl buyers who make the real money in international markets.

Woven throughout the central story are descriptions of the years of training which is required of a diver. Idriess details the work practices on a pearling ship and how they became safer and more efficient. For example, the British Admiralty solved the problem of divers’ paralysis which is caused by too much nitrogen in the diver’s blood. The solution was the ‘staged ascent’ which saved many lives. Staging was both a prevention and a cure for paralysis. If a diver came up distressed or apparently dead, he had to be sent back to the depth at which he had been working and brought up gradually.

There is a vivid account of the three days of the Japanese Riots in Broome during the seasonal lay-off in 1920, an example of the racial tensions always brewing in Broome and sparked by the growing profile of the Japanese. ‘Many a lugger had only one white man aboard, living lonely and aloof amid a mixed crew. On his management of this sailing hot bed of jealousies and sometimes hate depended the success of the season’s cruise.’

The later section of Forty Fathoms Deep details the ‘bushmanship’ required to work on the ocean and the sea floor. (Forty fathoms was the absolute maximum depth at which a diver could work.) There are the tides, the cyclones and hurricanes, the ‘tigers’ of the sea such as crocodiles, giant gropers and octopi, the devil-ray, sawfish, sharks and whales and giant clams all presenting special dangers. Fortunately, through vigilance, the diving suit, and help from above, the tigers of the sea are seldom fatal to divers.

There are beautiful descriptions of the plants and fish living in the sea, such as the turtle, a delicacy favoured by men and sharks. There is an extended description of the monkey-fish who frantically builds a sandcastle while his companion, the blue parrotfish, keeps guard, swishing away intruders with his tail. The monkey-fish is one of the ugliest creatures in the sea, while the parrotfish is one of the most beautiful. Divers call them Beauty and the Beast. The monkey, if deeply in love, builds a roomy bucket-sized home on the seafloor with hard walls of sand above it. He then mates but the female soon leaves to lay her eggs elsewhere. The blue parrot fish returns, and this unusual pair resume their friendship. The monkey is especially popular with divers for his bad temper and tempestuous behaviour if annoyed.

Another large flat fish with stripes on the back is a great lover, always seen with his ‘wife’ who he protects. He sometimes kisses her. While she rests, he keeps guard. The pair have big, kind eyes and the divers call them Romeo and Juliet.

We are taken to the sea floor to admire the strange beauty of the plants illuminated by the phosphorus given out by certain fish. ‘Lights come floating down … of fairy-like loveliness. They pass like tiny parachutes of illuminated silk glowing with the sheen of mother of pearl. From these hang clusters of red and green beads, and luminous tendrils drooping down all tasselled with glowing fire.’

The real-life characters are unforgettable, especially the villainous Con, a bosun on the Chamberlain until he retires to the comfort of Broome to chase women and practise his black magic. The volatile and dangerous Pablo Marquez and Simeon Espada, both of Chinese/Philippino background and from Singapore, belong to a secret deadly Chinese tong. There is Elles, the master pearl cleaner. We read of many storms and shipwrecks and the rebuilding which always follows, and the heroic efforts made by all to save the lives of those in peril at sea.

If you are fascinated by Australia’s labour and race relations, maritime history or Australian history and geography in general, it is time to revisit one of Australia’s most prolific writers, Ion Idriess (1889 – 1979).