Lilia is an Anne Kantor Fellow at the Australia Institute, currently working in the economics team.

She spoke on a range of current issues – stage 3 tax cuts, profit-push inflation, unemployment, and other labour market issues, with back-up from her colleague Jack Thrower.

This was a dynamic session, with a lot of slides to engage with, thoughtful presentation and analysis, and informed questions and commentary from the sizeable number of members present.

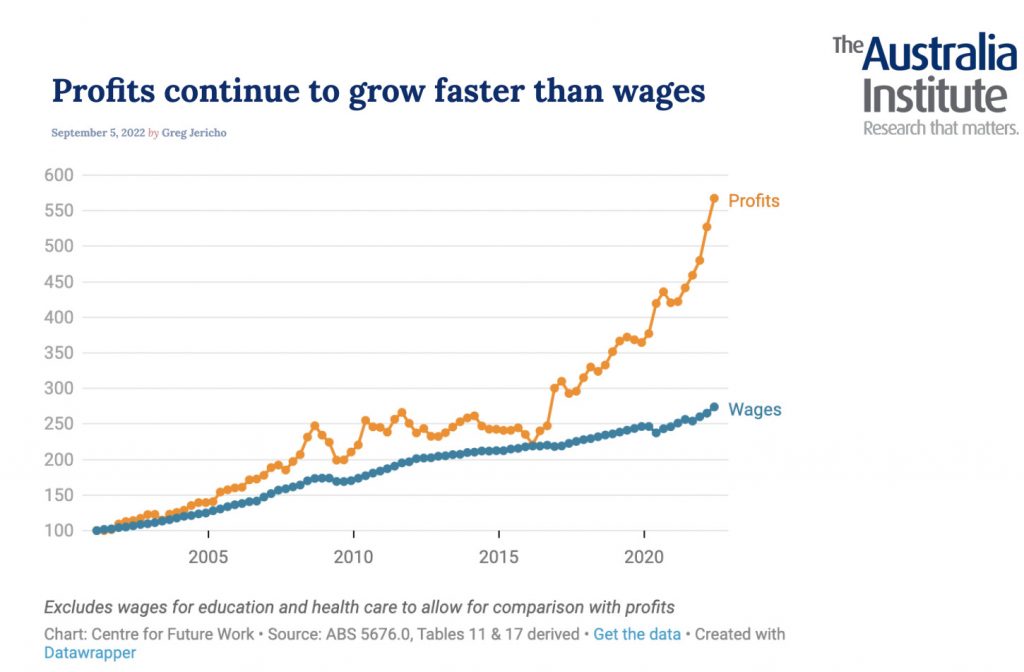

Here is just one slide to leave you wondering what is going on here:

To show our gratitude, our convenor, Garrett, gave both Lilia and Jack a beautiful Vintage Reds tea towel.

Lilia kindly sent links to a few important papers:

Here’s the press release for the July 2022 paper “Are Wages or Profits Driving Australia’s Inflation?” And the press release for the February 2023 paper Profit-Price Spiral.

Here’s a video explainer from Jim Stanford, and one by Greg Jericho.

Here’s the original profits vs wages explainer for the graph I showed, and another explainer video.

And last, there were a few questions about the gender pay gap. Here’s an article from Greg Jericho, “Yes, Australia’s gender pay gap is closing. But today’s working women will retire before it is fixed”.

You can sign up to receive the Australia Institute’s newsletter, here.